How it happened:

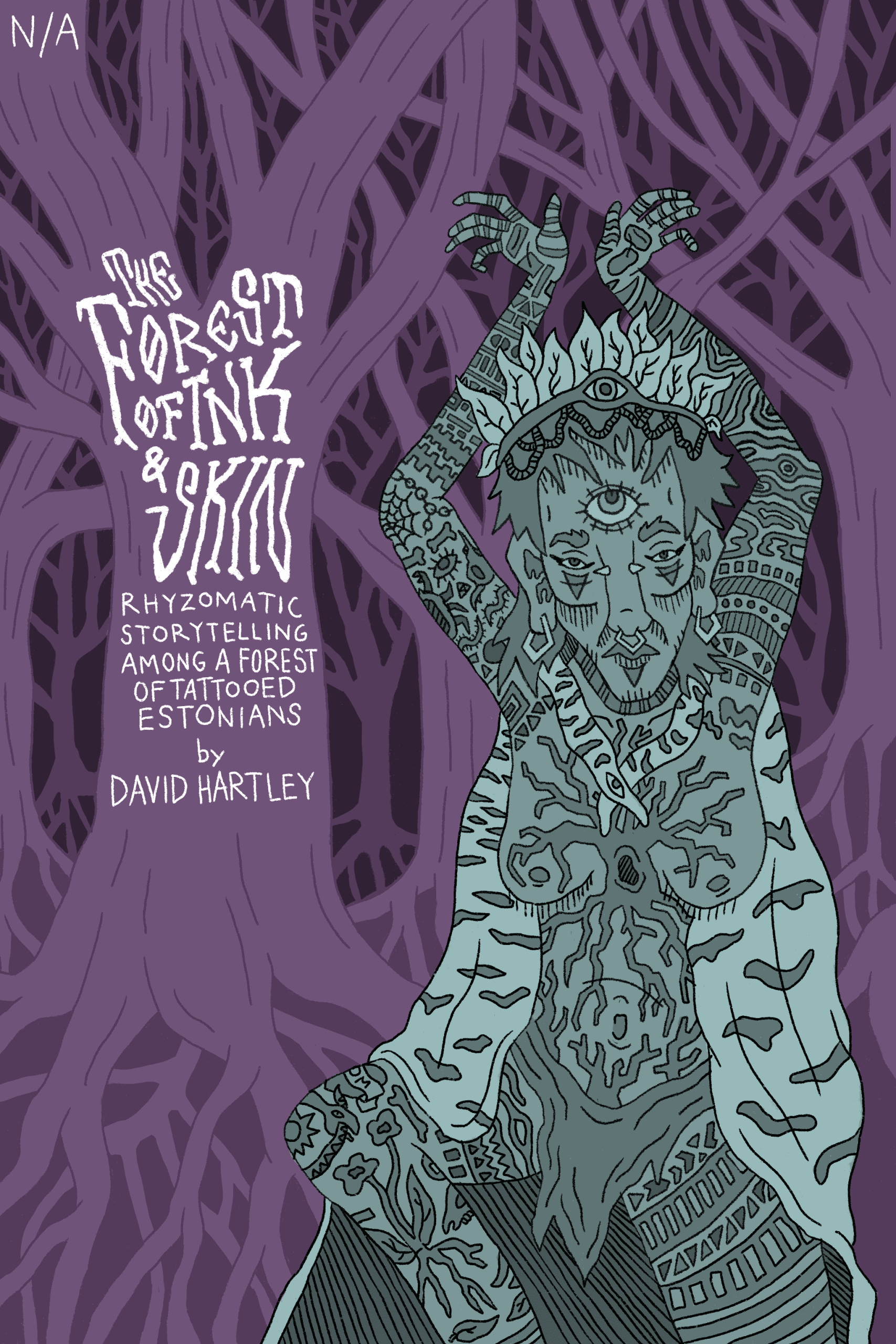

On the 11th May 2024 a temporary forest sprouted in a theatre in Tartu, Estonia. The trees were a gathering of around 50 tattooed Estonians, and the ink on their skin spoke of personal stories of triumph and heartache, pride and resilience, celebration and change. We instructed them to show as many of their tattoos as possible while dwelling silently in the darkened performance space.

I was positioned in the centre. I’d written a sequence of eight stories inspired by the same tattoos that now surrounded me. I’d also spent time reading Estonian folktales and mythology, I’d explored the edgelands of Tartu, and I’d visited the ancient mires and forests of the nearby countryside. The stories attempted to respond to these various nodes while staying rooted in the narrative traditions of folklore. The tattoos offered an obvious theme of ‘permanence & change’ which I soon found reflected in the Estonian landscapes and their accompanying mythologies. The resulting story sequence told new folktales of forests and their people who contend with nebulous technologies, eternal conflicts, and fragile interpersonal relationships. One of the stories, ‘The Artist’, is interwoven throughout this essay, like ivy embracing a tree trunk.

Back in the theatre, I’d fanned out the stories around me in an eight-pointed mandala. This is a pattern often found in Estonian folk cultures and was also to be discovered inked across the shoulders of one of our trees, somewhere in the shadows. At fifteen-minute intervals, small groups of audience entered the space with torches. They were told to roam the forest, shining their lights on the tattoos while I read out one of the tales. At the end of the story, that audience group would exit, and the next would enter soon after for the next reading.

Beneath it all looped a soundscape composed by UK electronica artist Rickerly that featured birdsong, the swish of the wind in the canopy, long-held drone tones, and sonic hints of distant machinery. A chasing sequence of lights pulsated overhead, and a thin haze of smoke filled the air. The tattooed trees would sway and shift, a few fell gently to the ground, others crouched like stumps, one did a handstand as if uprooted, her roots turned upwards to the sky. Sometimes I would roam towards particular tattoos, other times I would stay seated in the centre and let the audience make their own connections.

We cycled this for four hours so that each story would be read twice. Two full turns of the mandala.

This was The Forest of Ink & Skin.

The Artist: Part 1

On the edge of a mighty forest lived a woman who was all alone in all the world. No-one knew why she lived alone. Some from the town say that she was left in the forest as a baby and raised by bears. Some say she had a husband once, but he was so cruel to her that she killed him and burned his body in the fire she uses to heat her sauna. Some say she’s not a woman at all, but a witch who is also a werewolf. But she kept herself to herself and was no trouble, so the townsfolk let her be.

But the world turned, as it does, and the times changed, as they do, and the town swelled and became a city, bursting at the seams.

And from that city came a man.

He had silver hair, a golden suit, and bronze shoes, and he ate dry food from boxes instead of the plentiful food offered by the forest. He walked with great confidence, his head high and his arms swinging, as if pretending he were a giant taller than all the trees. He thumped a fist on the door of the woman’s house. Against her better judgement, she let him in.

“Why do you live here all on your own?” he asked. “No husband, no lover, no children, not even a dog or a cat. Aren’t you lonely?”

It took some persuasion to make the woman speak, but the man had a silver tongue and lots of patience. Soon enough, the woman was telling the tragic tale of her life. She had not been abandoned as a baby, she had never married nor killed a man, she was no werewolf or witch. Her tale was much more complex, much more difficult to understand, and contained just as much love as it did pain. Later, when the silver-haired man was questioned he could not remember her story, for he had not really been listening. His mind was typical of the men from the city: always busy thinking of other things.

“There must be something that you want?” he said. “Something you desire most in all the world?”

She said that she had everything she needed right here in her house with her sauna, and the forest.

“That can’t be true,” he said. “You need a husband?”

No.

“You need children?”

No.

“Then surely you must feel the need to travel beyond the forest and see the rest of the world?”

She paused. She said no, but he heard her hesitation.

“Aha,” he said. “You have wanderlust!”

She had never heard this word.

“No,” she said, more firmly. “True, I am curious about the world, but I have no desire to leave this place.”

“Well, that’s easy,” he said, smiling a smile with no real smile inside it. From his pocket he produced a strange, glowing device and gave it to her. He showed her how to use it, and it showed her the world.

She was soon entranced.

“You can keep this one,” he said. “But I want something in exchange. We’re building a harbour. Boats, ships, and docklands that look out over the sea. Our city needs to keep growing and the ocean cannot stop us. Naturally, we need lots of wood. I will be taking the forest.”

The woman nodded because she was not really listening. She was looking at pictures of harbours and docklands and boats and ships, and she was looking at the sea and wondering how far it stretched.

“I will return for it in one year,” said the man, and strode out with his head high, his chest up, and his arms swinging like axes.

How it came to be:

The core concept of The Forest of Ink & Skin had sprung from the head of my collaborator, the Tallinn-based performance artist Henri Hütt. We had wandered Tartu together seeking inspiration, and he’d struck upon the idea of an audience doing the same. He envisioned a ‘rhizomatic story experience’ where an element of ‘soft participation’ might be created through an audience actively rambling through tattoos. Perhaps, he suggested, my story might mention an owl, and in that same moment the various torchbearers could be looking at a feather, or the mandala, or a mouse, or a skull, or the word ‘survive’, or, indeed, an owl. In this way, each audience member makes their own symbolic associations between what is seen and what is heard, perhaps enjoying thematic resonance or instead experiencing the disturbance of dissonance, or something more nebulous in the hinterland between the two.

And while the tattoos had directly inspired the stories, that unity was eroded by the roaming audience who encountered these alternative montages. A skull tattoo might portent a character death that never happens, or a devil sparks a fear that proves misguided, or a heart suggests a romance that is unfulfilled. In a sense we’d created a strange edgeland of narrative where steadfast symbolic connections are put under strain and new uncanny linkages spring up in their place.

Of course, the audience had other alternatives. They were also free to switch off their torches and turn away from the tattoos to focus entirely on me – and, indeed, some did exactly this. In contrast, there were many others who roamed with determination from one inked body to another as if this were an art exhibition (which, in a sense, it was), and seemed to completely ignore the story being told. This too was a legitimate experience, especially for those few who may have struggled with the language barrier (my stories were told in English). Whatever they decided, our main intention had been to liberate the audience from their anonymous, homogenous block of relative safety and instead let them loose to embrace a degree of chaos.

To be rhizomatic, according to Deleuze & Guattari, is to resist the ‘arborescent’ and hierarchical way of thinking, with branches sprouting from branches all derived from a central trunk. Instead, we are to adopt a planar, horizontal network with no overall coherence or order, where starting points and ending points are not so easily defined. In this sense, while our tattooed participants became trees for the afternoon, the rhizomatic experience better evoked the imagined mycorrhizal network beneath our feet; the ‘wood wide web’ of fungi fibres that spread from tree roots to tree roots carrying messages and information. There was a visual sense of this during the performance. We kept the experience on a horizontal plane, no one person any higher or lower than anyone else, myself included. We had no riser stage to step onto, and the audience were not in their raked seating. The traditional theatrical spatial hierarchy was eroded.

This was partly how I was able to brush off those audience members who seemed not to be listening to my stories. We had created a space of wandering freedoms rather than a constricted focus, an almost neurodivergent theatrical expansion that accommodated the differing needs, attitudes, and intentions of the non-homogenous visitors. I also came to realise that I did in fact have a dedicated second audience in the form of the tattooed trees, many of whom reported entering a heightened mindful state as they embodied the forests I repeatedly invoked in my tales (especially the carved one included here in ‘The Artist’). By the second half of the four hours, they were making links between the stories and showing me relevant tattoos that I had not previously seen. I was most delighted to discover a hedgehog on someone’s arm given that the final story in the sequence ends with a hedgehog with ink in its spines. The rhizomatic network was feeding messages back to me.

I’ve deliberately invoked neurodiversity here as a rhizomatic offshoot from my previous project, where I studied the relationships between autism and fantastical narratives for a Creative Writing PhD. I’d come across the work of radical French educator Fernand Deligny who had, across the 1960s and 70s, fiercely resisted the institutionalisation of autistic children. Instead, he’d developed a form of cartographic observation where young autistics are given time and space to roam as they pleased while Deligny mapped their ‘wander lines’. These maps were subsequently used as navigation aids during the therapeutic and socialisation activities of his clinic.

Deligny’s idea was to allow the world to bend around the autistic people, rather than forcing the autistics to fight their instincts for the sake of fitting into a world constructed around neurotypicality. Such thinking is a core tenet of the neurodiversity movement in the present day, and this ‘neuroqueering’ of the world offers a fresh approach to the deconstruction of the stubborn hierarchical structures of narrative and performance. I like to think we all left our ‘wander lines’ on the floor of that theatre. Overlapping loops and circles of audience, trees, and performer, each telling their own idiomatic tale of the desire to see and be seen.

It would not be a wholly rhizomatic picture. Seen from above, it would be me at the core with the audience circling, and the trees drifting slowly around in the same orbit, like satellites. But I think also of the pattern of the torch beams, the ‘castlines’ perhaps, that tell a more rhizomatic tale as they dart from tattoo to tattoo in a divergent quest for coincidence and discordance.

Something had been freed, I like to think, to run wild inside our forest.

The Artist: Part 2

Later, the woman was alone in her sauna.

There was a great storm shaking the forest, and the branches of the nearest tree were tapping furiously at her window. Soon enough, the strange device stopped working, so the woman had to come back to her own mind. She remembered what the man had said, and it upset her immensely.

She ran from the sauna and sought out the wisest trees of the forest.

First, she visited the eldest birch, the kindest and most understanding, and begged for its forgiveness. A birch does not hold grudges, for it offers patches of its silver skin to write love songs and memories. The birch, in all its wisdom, could see she had been tricked by the silver haired man and his hypnotic device.

The birch said: “You must take the device to the eldest oak and place it inside the hollow. The oak will examine the device and it will soon know what to do.” And the birch gave her a coat of its silver skin to protect her from the rain.

She hurried to the oak and kneeled at the roots, begging again for forgiveness. While the oak was grumpier than the birch, it was also the sturdiest and wisest of all the trees in the forest. It took the device in its hollow and swallowed it. The oak began to understand new and wonderous things. It learned about the strange age of glowing devices that had arrived so suddenly in the last few rings of growth. It saw how they connected, and how the humans were dragged along in an agonising cycle of high joys and deep pains. Most of all, it saw possibility. Endless possibility. And soon it had a plan.

The oak placed a crown of its leaves upon the woman’s head to grant her its wisdom. “I will keep hold of this device,” it said, “it is not for likes of you. Now go, to the eldest pine, who will give you the items you will need.”

With her cloak of silver skin, and her crown of leaves, she hurried on to meet the pine. Again, she fell to her knees and begged for forgiveness. The pine was the most artful and cheeriest of trees. It had long forgiven the woman even before she transgressed, knowing full well that she would never harm a living soul. The pine knew of the oak’s plan, and happily agreed. It bled out a barrel of its inky sap and gave her a sack full of its sharpest needles.

“Well, well,” said the pine. “You’re going to create art, my dear. A picture, if you please, upon every tree in the whole forest, but a different picture each time, of course. And then go into the city and tell all the people to come see your work. It will be fabulous.”

She was very scared, as she had never attempted to create art before, and she had not visited the city for a long time. The pine laughed and gave her a cone to place beside her heart, because a pinecone is a work of patience and pattern beloved by young and old.

She spent a moment practicing on the trunk of the pine, drawing two stick figures fighting with swords. It was crude but it was delightful, and for the first time since leaving the sauna, the woman felt a glimmer of hope.

What it meant:

During my trip to Tartu in February 2024, just as the writing of the stories was starting in earnest, I escaped the hard Estonian winter for a couple of hours and took to the cosy warmth of the Elektriteater cinema. The auditorium was packed, not a spare seat in the house, and the Estonians were uncharacteristically fidgety and vocal. The film was Vara Küps (‘Vertical Money’), a documentary by Martti Helde concerning the current management (most would say mismanagement) of Estonian forests. Slick businessmen would appear on screen to justify the excessive logging and the unhealthy cutting methods, raising incredulous laughter and barbed comments from the auditorium. The tension in the room was palpable.

Estonians have been known as ‘forest-people’. Around 60% of the Estonian landscape is forest (compared to around 12% of the UK), and their histories, religions and mythologies are deeply intertwined with woodland. For philosopher and semiotician Valdur Mikita forest covered landscapes are ‘an essential part of the sense of home for Estonians’, and he suggests that forests have been ‘an accelerator of consciousness’ for the nation. He argues that forests are where ‘periphery accumulates’ and spending quiet, meditative time within them ‘supply a culture with the unusual and keep it alive’ (Forestonia, Estonian Literature Centre, 2020).

He also tells of the importance of the ‘home forest’; the area of woodland closest to your home which is adopted as a sacred and treasured place. You’ll go there to forage for berries and firewood, you may build your smoke sauna within those trees, you may even find yourself a warden of an ancient and sacred pagan site. Historically, Estonia was one of the last holdouts on Christianity, abiding for hundreds of years as a stubborn pagan pocket, and there are signs throughout the country that these earth-beliefs never fully went away. This may have been in large part due to these forests, where sacred spaces could stay more easily hidden and preserved. And while Estonia is today considered one of the most atheist countries in the world, there is a clear spiritual intensity for nature within Estonian hearts, with forests as a central pillar of the pantheon.

Estonian trees have persisted as protectors and providers of sanctuary. During World War II, when Estonia and the other Baltic states were tossed between Soviet and Nazi control, the forests became the fertile arena of resistance. The ‘Forest Brothers’ freedom fighters took advantage of the generational knowledge of the woodlands and became a persistent thorn in the side of the oppressors. While the Stalinist regime eventually quashed these efforts, the legacy of this woodland brotherhood echoes down and can be felt today in the proud and unwavering Estonian support for Ukraine.

Today, many of the urbanised Estonians will retain a modest ‘country house’ at the edge of a forest to decamp to during summer – locations that proved vital during the COVID pandemic. Wood is everywhere in Tartu; most of the houses are made of wood, their tourist nick-nacks are wooden kitchen utensils, and in the colder evenings the streets fill with the heady scent of woodsmoke. It was no small thing to choose the forest as our creative setting; the trees intertwine with Estonian existence as if their blood were sap and their skin, bark.

And yet, despite all this, Vara Küps reveals a governmental distain for the preservation of woodland heritage. Forest felling has accelerated in recent years, and large swathes of ancient woodland are being aggressively cut in pursuit of profits. Wood, of course, is one of Estonia’s key exports, and the forestry commission argue that harder winters and growing populations, both within and outside Estonia, require more wood as a source of fuel. But activists contend that protected forests are being shadily re-categorised and felling stats are being fudged to accommodate aggressive expansion. Environmental concerns are also being ignored as monoculture pseudo-forests are cultivated for the purposes of logging, resulting in unhealthy, lifeless woodlands with little other flora or fauna. The pointed use of drone shots throughout Vara Küps show the devastation wrought on the landscape. Bare and boggy arenas scratched with the black track lines of the harvesting machines, the scarring wander lines of ecocide.

The story sequence of ‘The Forest of Ink & Skin’ makes regular contact with these fragilities. In one tale, a future city has carefully constructed sanitised ‘zones’ of nature, including the most extreme version of a monoculture forest, and has embedded folkloric fears among the people to stop them straying beyond the boundaries and into the wilds. The girl who disobeys is reunited with animal life and transformed into a witchy figure more radical than the city folk have been allowed to imagine. In another, a family collectively loses their memory after one member, the youngest, is cursed for neglecting the home forest. Returning to the trees restores a fragile form of harmony, but the ancient forces of the woodland fade into an unheard distance, doomed to be forever out of sync with human modernities. I hope ‘The Artist’, included here, speaks for itself.

Like our audience, the stories meander and drift and make unexpected turns. They are pointedly self-aware, asking questions of the narratives we construct for ourselves when we use them to justify inharmonious actions. Obvious conclusions are resisted, questions are posed and left unanswered, and throughout the sequence the forest abides as a ‘bewitching landscape’ (Mikita, Forestonia). It persists as often as it falls, it outlasts and outlives, sometimes shunning our fairytale foibles, sometimes embracing them wholeheartedly. Much like our tattooed trees, the forests in the stories are temporary, private, mysterious, and lead their own lives away from the glare and the torch beams of visitors.

Vara Küps unveiled to me a febrile debate that I was wholly unaware of, reminding me of the similar debates we’re having in the UK concerning the poisoning of our bodies of water. It also helped to reveal the cultural importance of asking a group of Estonians to embody a living forest of temporary trees and inviting another group to explore it. The rhizomatic experience within the theatre space extended far beyond those darkened walls, reaching into the depths of the home forests, ancient forests, and sickly forests just beyond the city limits.

The central presence of the tattoos, I hope, emphasised a theme of defiant permanence that helped strengthen these mycorrhizal narrative lines. Here, carved on the skin-bark of our sturdy oak-humans were hieroglyphics of hope, icons of inspiration, and runes of resilience, the exact details and reasons for their origins deliberately obscured. Instead, the mere existence of the tattoos urged us forward by showing that change will happen, but our destinies are shaped by what we choose to do.

The Artist: Part 3

Every day of that year from dawn to dusk, she went from tree to tree sketching and etching, wearing her cloak of birch and her crown of oak, with the cone of pine snug beside her heart. On the tree closest to the city, she drew an eight-pointed mandala with a butterfly at the centre. It would tell the townsfolk that there was a transformation underway. On the tree furthest from the city, she drew herself, her arms crossed over her chest, and her head replaced with blooming flowers and stretching leaves, so that she could always remind herself that there are ways out of every difficult situation.

And on the tree at the very centre of the forest, not far from the eldest birch, she drew a great dragon, borrowing all the colours of the forest, from the berries to the beetles, and the tree responded by growing twice as tall so that the dragon could look out across the canopy, ready to spring to life should any felling begin.

It took her almost the whole year but with one day to spare, and only one needle from the pine remaining, and just one single drop of its sap, she had etched pictures on every trunk of every tree throughout the whole of the mighty forest.

There was but one task remaining, and she barely had the energy to do it. But the dragon roared from above the canopy, roses bloomed from her cheeks, and the mandala swirled through her mind and drew her to the edge of the city.

With the final needle and the last drop of sap, she fell upon the door of the house closest to the forest and wrote the words: ‘Come and See’. Then she turned and walked back towards the forest, knowing full well that this journey would be her last.

When she reached the mandala, she just had enough energy to look behind. There was a vast crowd of people following her and they all had the same strange device as the man who had visited her almost a year ago.

And the great tragedy of this tale is that our artist died on that spot thinking that she had failed. Her final thoughts were these: that all those people had been hypnotised by the silver haired man just as she had been, and they were going to use those devices to destroy the trees and build the wooden city to choke the distant sea.

But the trees knew differently. She had not failed. The oak’s plan had worked perfectly. The people came with their devices, but they did not cut down the trees. They explored the forest to every corner and every inch, and they marvelled at the work our artist had done. And with their strange devices, they showed her work to the rest of the world and within the space of just a few brief hours, the plans of the silver-haired man were stopped. As for that man, he was driven out of the city and told to go elsewhere. As for her house, it became a shrine for her mighty work.

As for the forest, it lived on, the trees aching in the pain of bearing her art, but they stayed standing for as long as they could manage, which was many, many years. And by the time the last painted tree had fallen, there were already many new trees in place.